EXUVIAE

Our connective tissue gives our bodies form and cohesion. The quandary of a thesis found me looking for the connective tissue that binds my work together, supports it, and gives it recognizable form. While percolating on the matter, I gave myself permission to dig into my archive of images and bring out those that I did not consider “work” to pair alongside the images that I do consider formal work. As I contemplated the mishmash, I wrote down words that came to mind: kin, shed, molt, fell, identity, mask, growth, change, loss, abandonment, mortality, memorialization, memory, time, nostalgia, absurdity, humor. That brought me to the title of this exhibition: Exuviae.

Exuviae are cast skins, shells, or other coverings of animals. The connections in my work are found in that which is shed and consequently remembered or memorialized. The foundation of growth and change is that which is lost or abandoned. The ensuing nostalgia provides room for the humor and absurdity of identity to transform over time and finally to die.

STUMPED

It was the summer of 2020 when I arrived in Albuquerque. I was eager to explore my new surroundings and began taking long walks in the cool of the evening. Pandemic precautions kept most folks at a distance, but I was getting to know my new neighbors by the things that adorned their homes and yards. As I walked, I noticed an uncanny proliferation of tree stumps—most knee height but some taller than I. These arboreal vestiges felt lonely, sad, and a little quirky. They gave me pause and brought to my mind the Woodmen of the World tree-stump tombstones that dot cemeteries across the country.

Woodmen of the World is a fraternal organization dating back to the nineteenth century. The Woodmen believed in the dignity of a marked grave and so provided for their members, as part of the death benefit, a tombstone shaped like a tree stump. More than a few folks bought in to the idea. To warrant such a marker one need not be a lumberjack; the sawed-off limbs were meant to symbolize a life cut short. As I contemplated and compared the odd ruins of urban trees to those stone monuments carved to resemble them, I wondered why anyone would want to have a tombstone in their front yard.

BANANAS

When I left the South and moved to the North, I learned that much of what I regarded as normal was not regarded as such in my new home. Case in point, banana and mayonnaise sandwiches. When I mentioned the combination, those Yankee heathens turned up their noses and made rude noises. Banana sandwiches were a staple of my childhood diet. I thought they were delicious, still do. To make a good one, you need soft white bread, a banana that has been around long enough to obtain a fair number of speckles on its skin, and creamy dreamy Duke’s mayonnaise. You may or may not add peanut butter, you won’t be faulted either way so long as you realize that the real magic lies in the marriage of the banana and the mayonnaise.

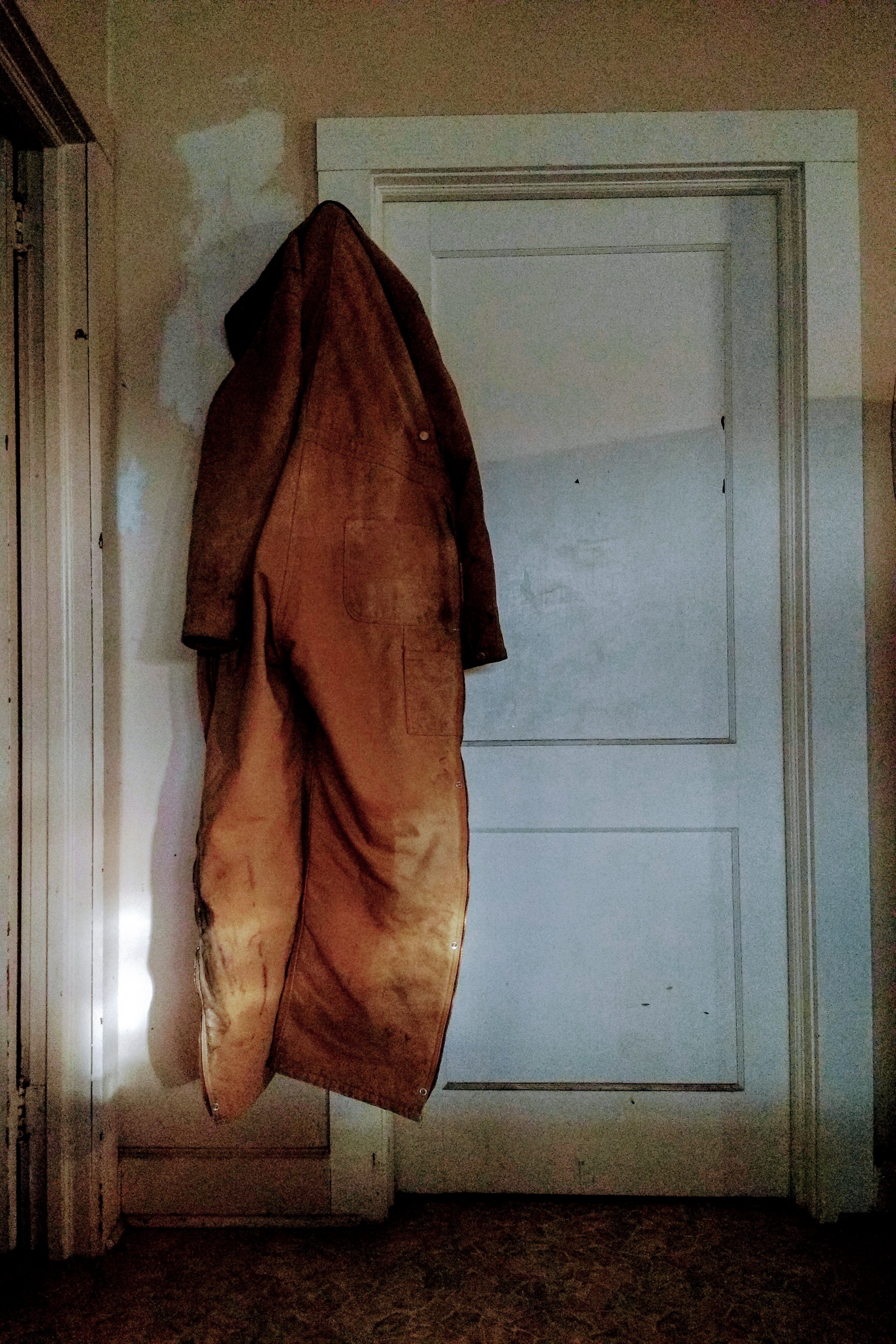

YELLOW HOUSE

The yellow house is an abandoned property located within walking distance of my former residence in Bakersville, North Carolina. I would stop in every so often, to wander through the rooms, investigate some pile of papers a little closer, or cautiously peer inside a cupboard. I even tried on some of the clothes hanging in the bedroom closet. They were much too small for me. I did not know who lived there or why they left—nor was that story crucial to my relationship with the space. Instead, I sensed a calming vitality in the things that remained despite their fall into desuetude. In the early mornings the light was soft, all was quiet, and I felt at ease.

EXHALE

On the winter solstice of 2015, I participated in a “sweat” in a forest in southern Georgia. I was in a bad mood that day. The night before had been cold and sleepless and I had my doubts about the sincerity of the people I was with.

My mother died one spring morning in 2010. I was by her side. The windows had been opened so that she could hear the birds singing. I remember so clearly the arrival of dawn’s chorus. My mother had been in the process of dying all week and was heavily drugged with morphine to ease the pain of her disease.

When I was a child living at home, my mother and I were able to communicate without words—we just knew what the other was thinking. Moments before she died, my mother communicated with me again in that way. She told me that I had better get dressed and ready because things would go quickly afterward. I got up and left the room to dress. As soon as I came back, she was ready to go. I held her head in my hands as the last breath passed from her mouth.

Once the fire was hot enough for the sweat, we all squeezed into the lodge. It was an intense sensation. At some point during the ceremony, I felt a breath come up from my belly, through my chest and out of my mouth. It was not my breath that I exhaled. It was my mother’s breath that I had been holding. Letting it go was a tremendous release.

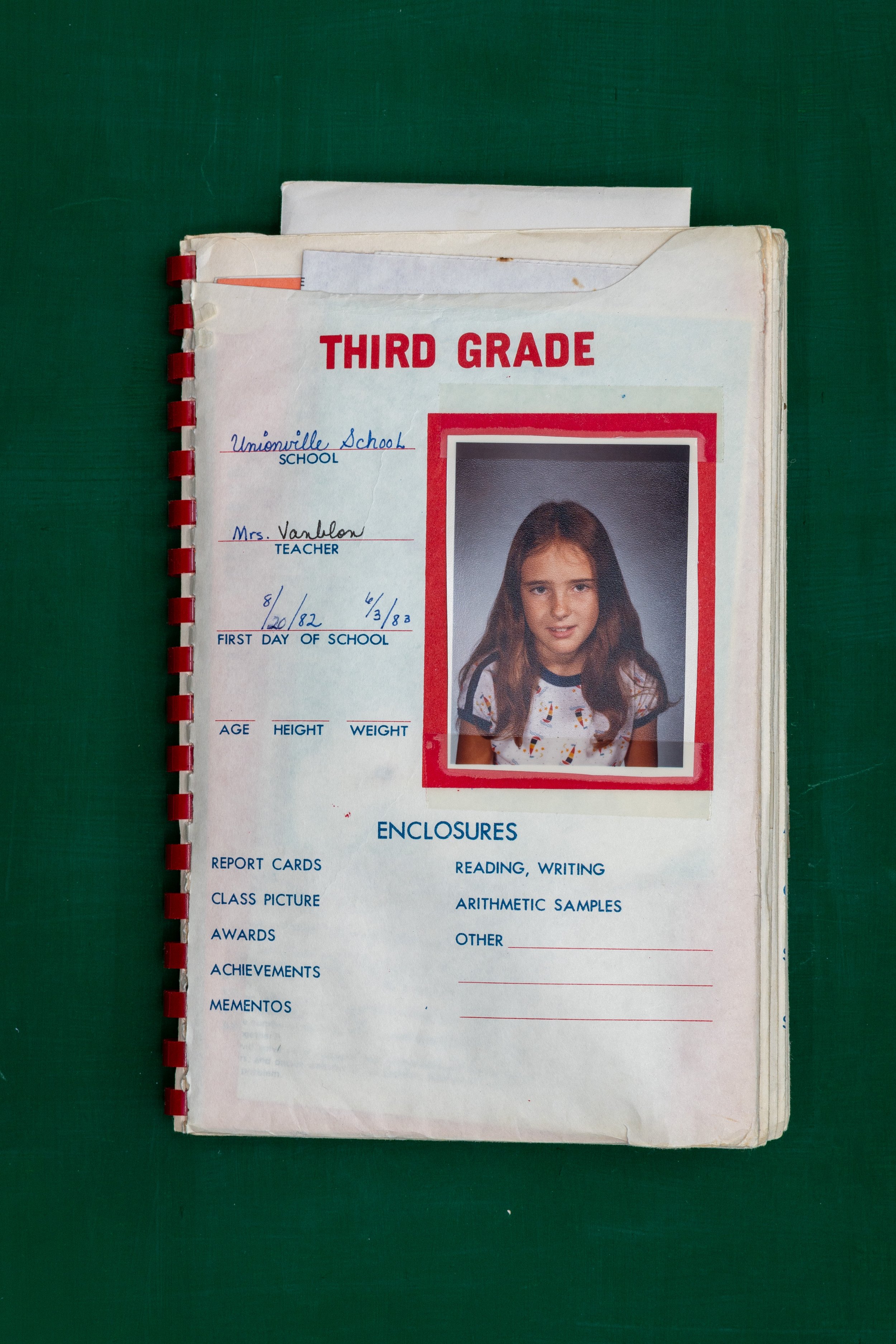

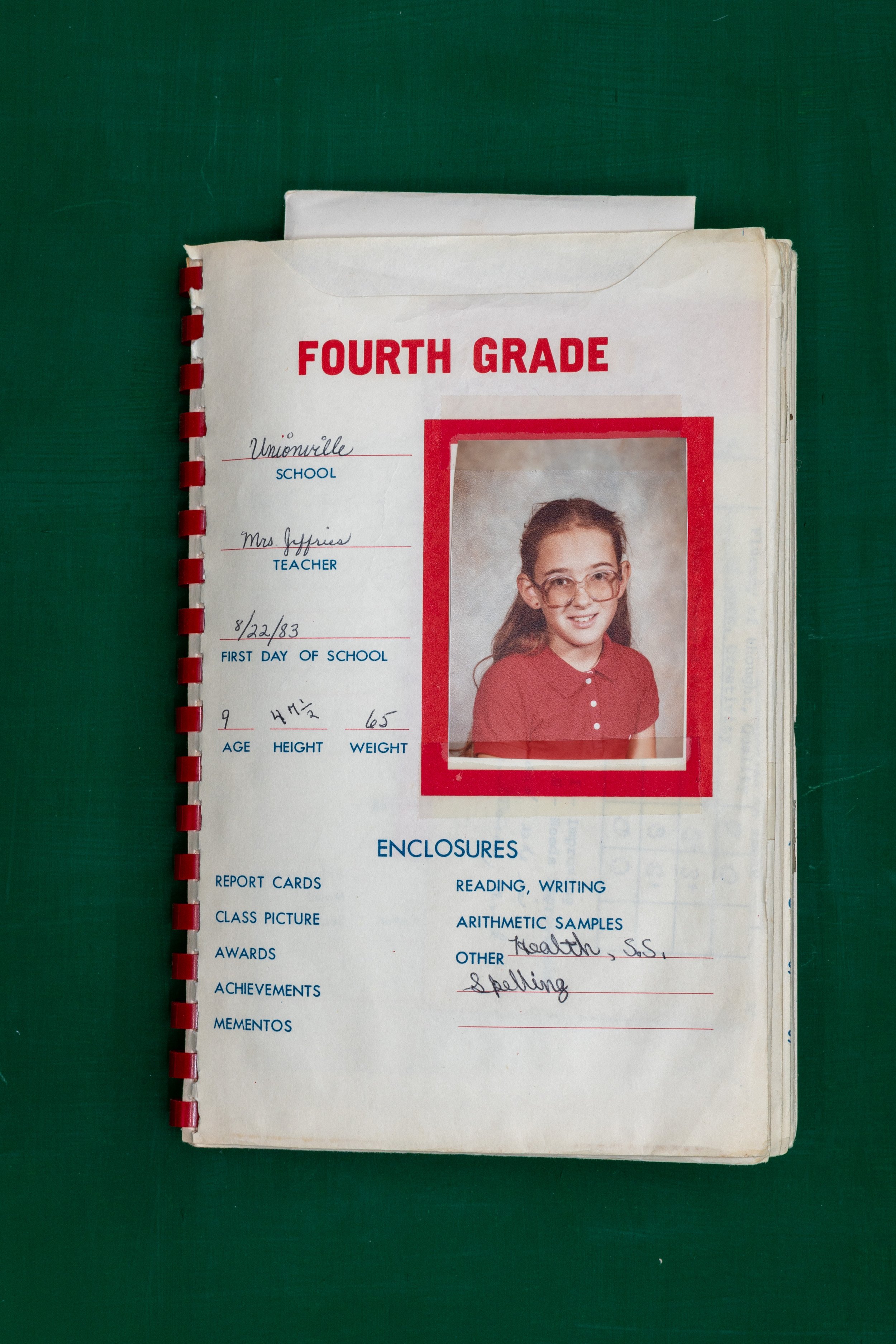

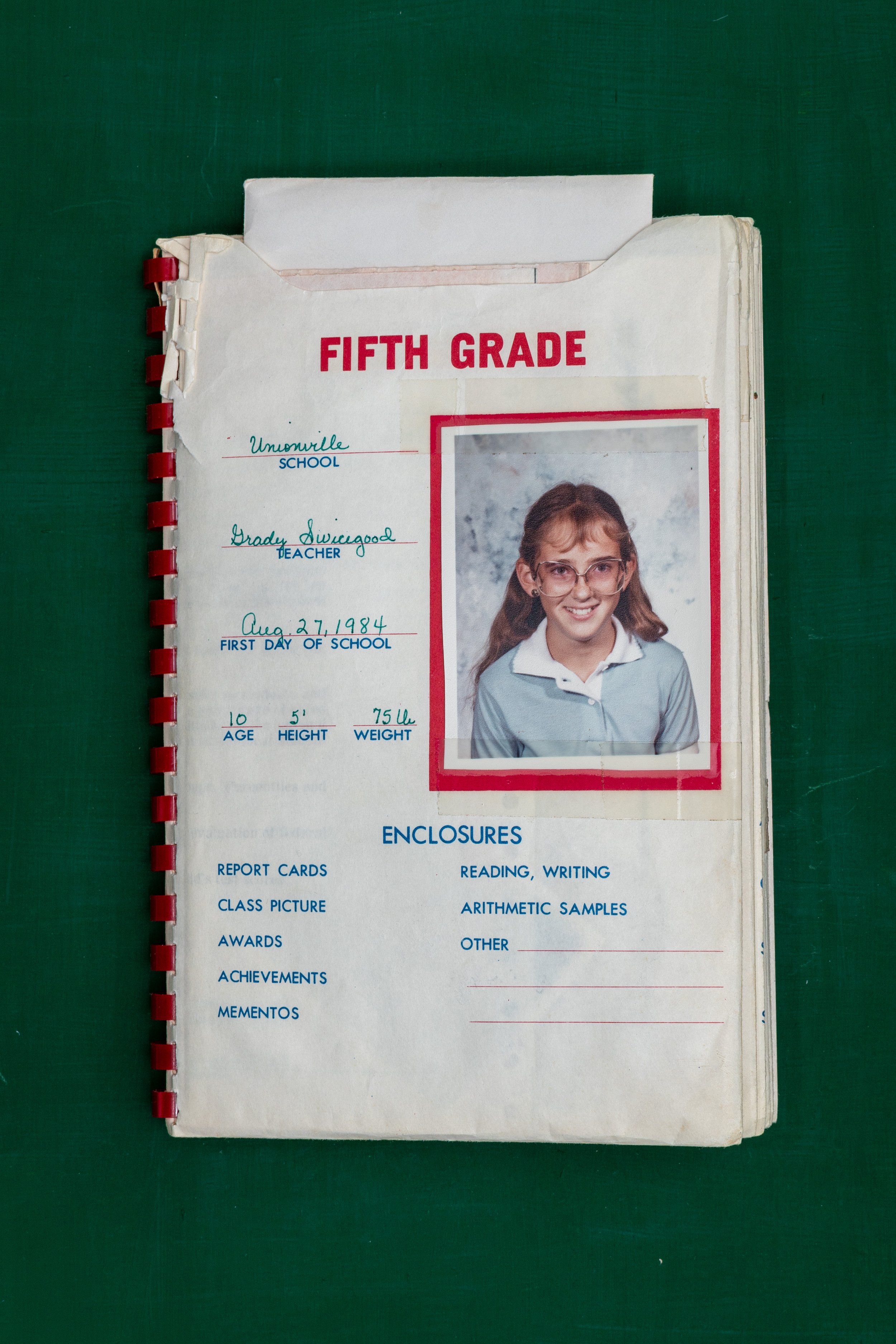

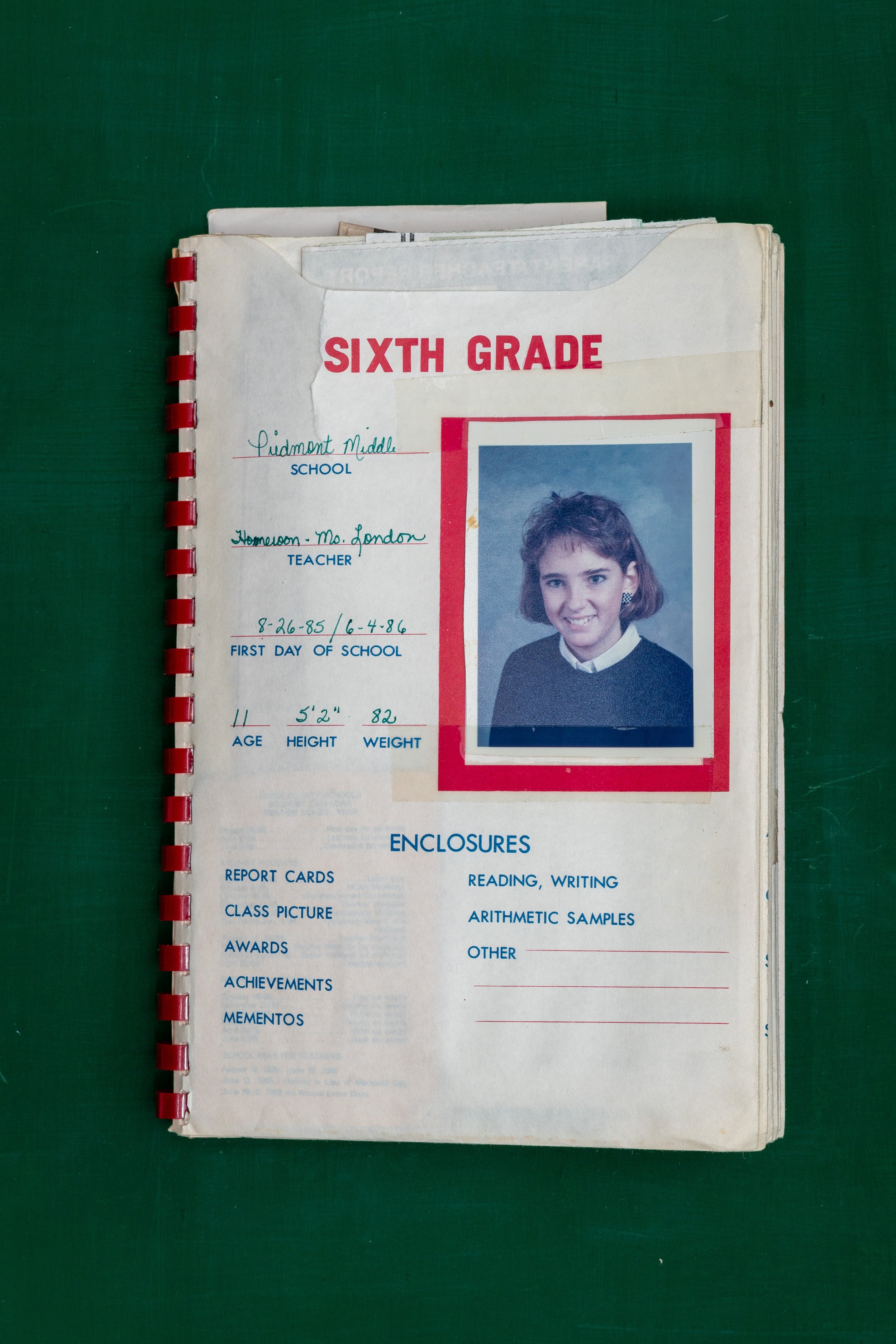

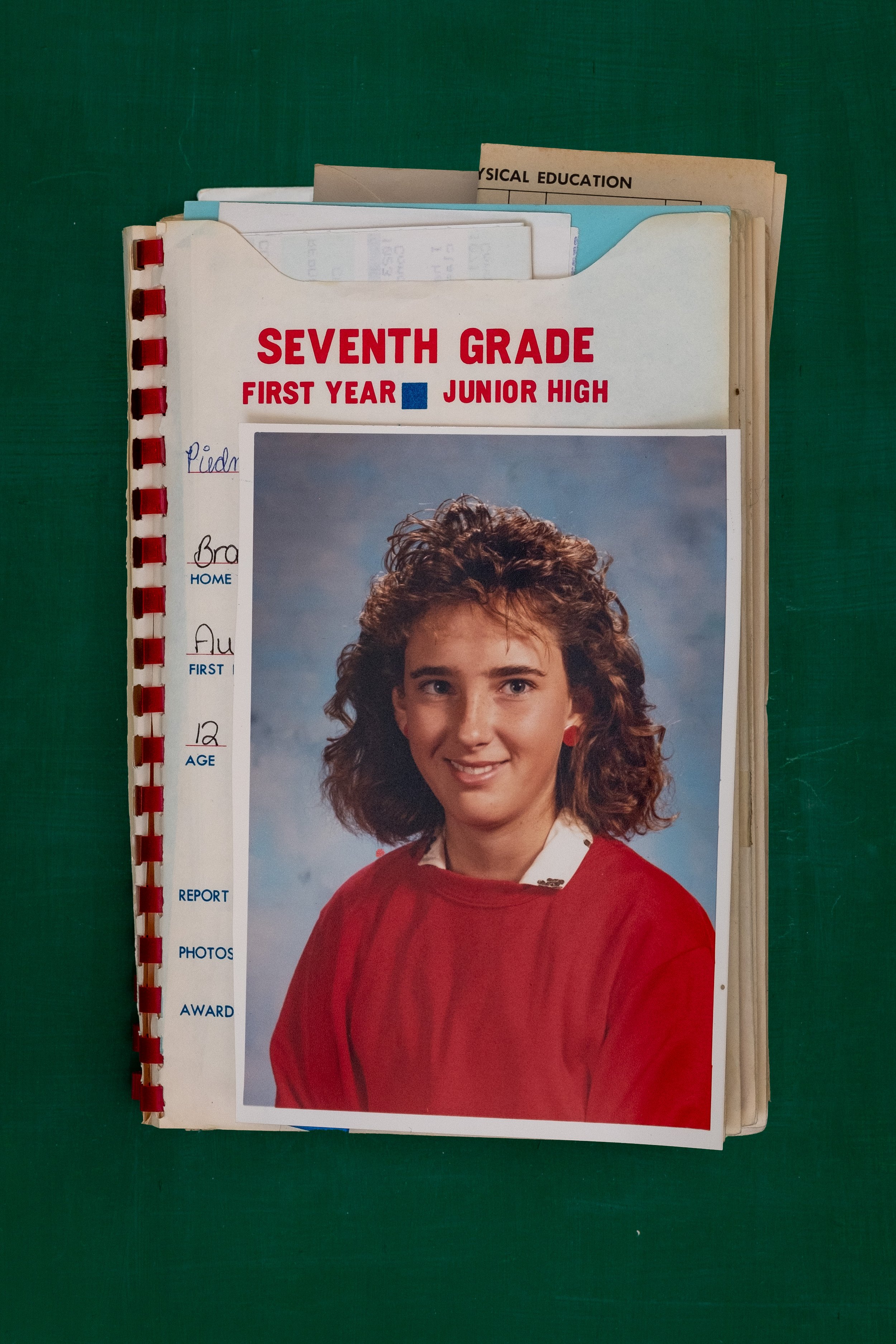

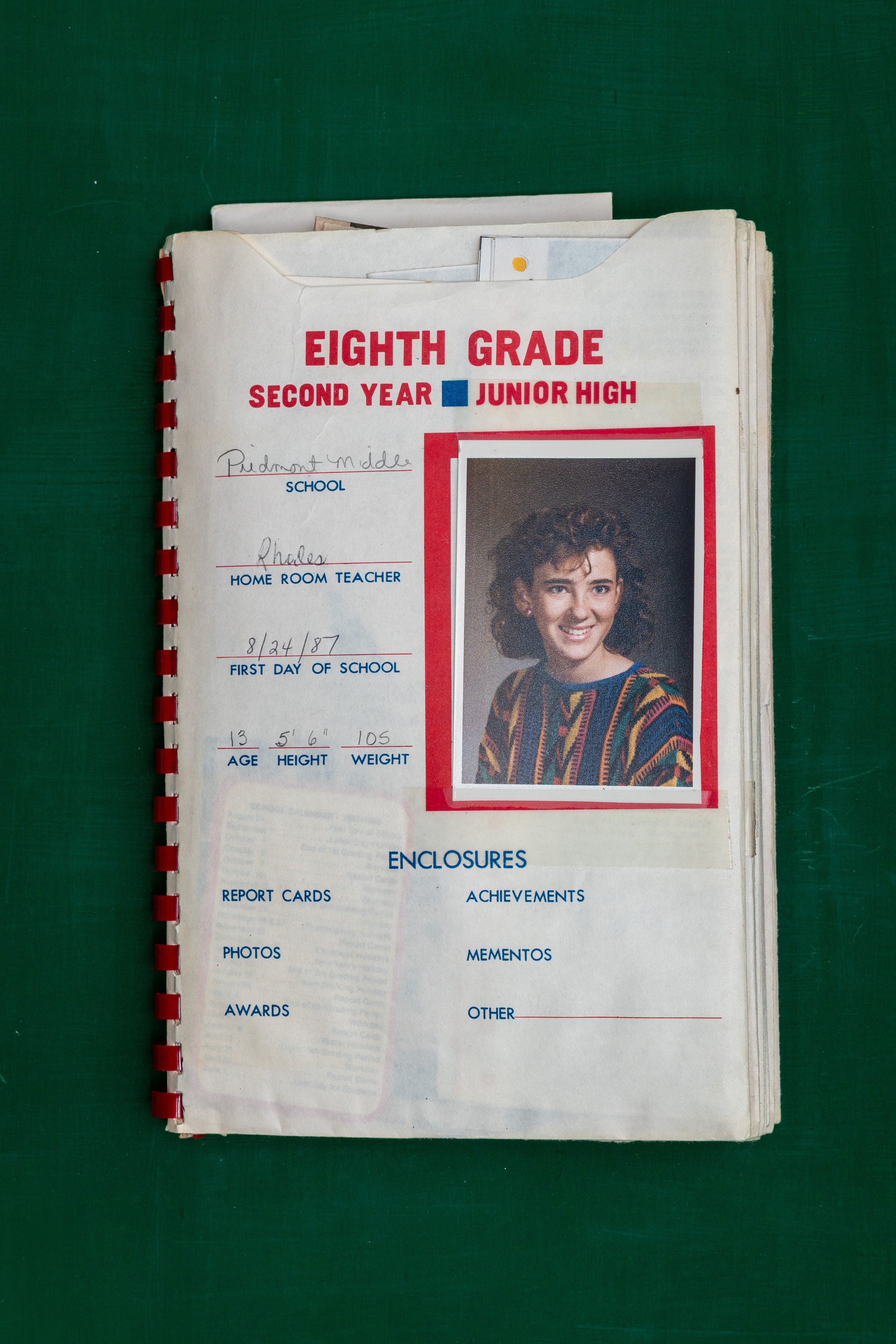

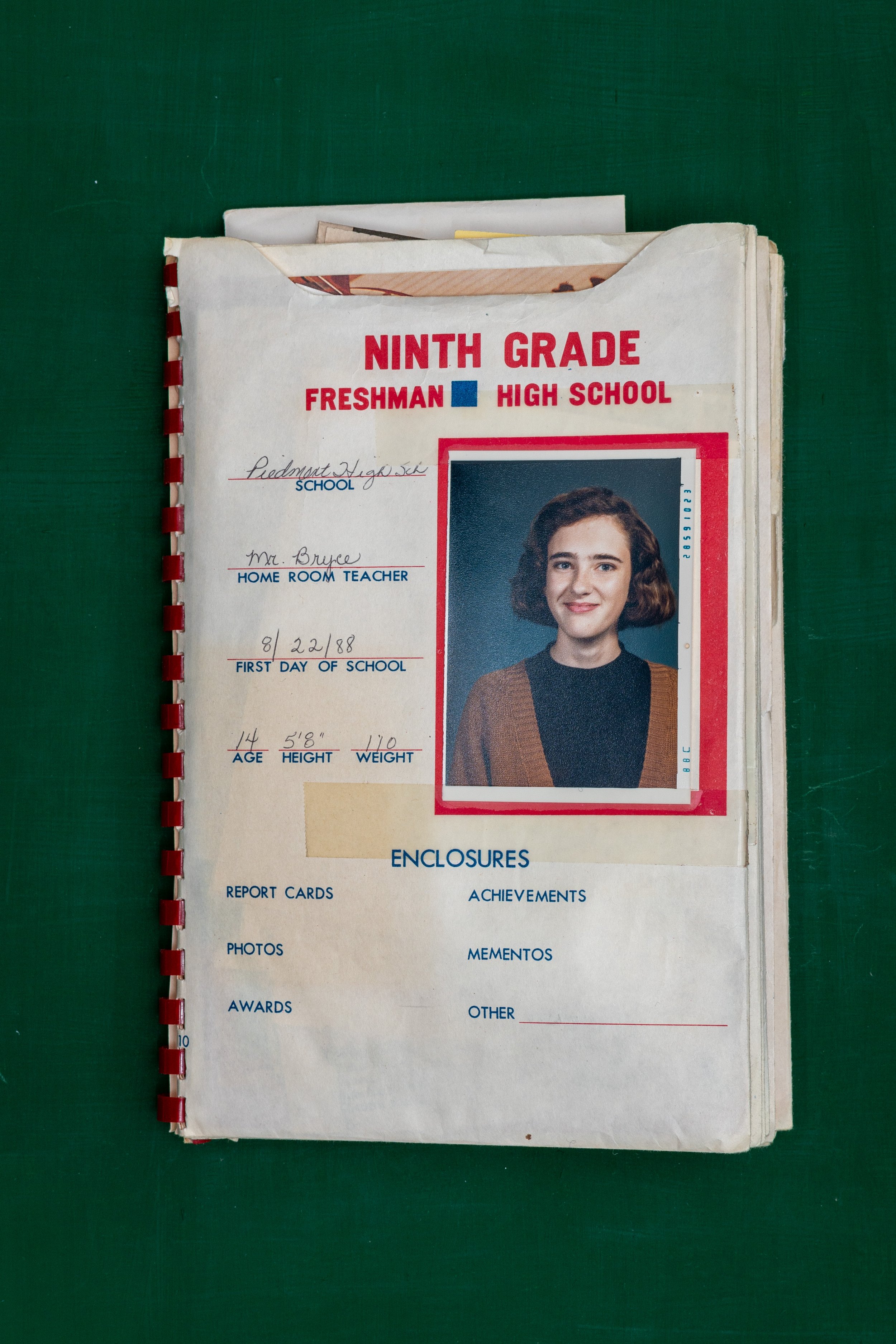

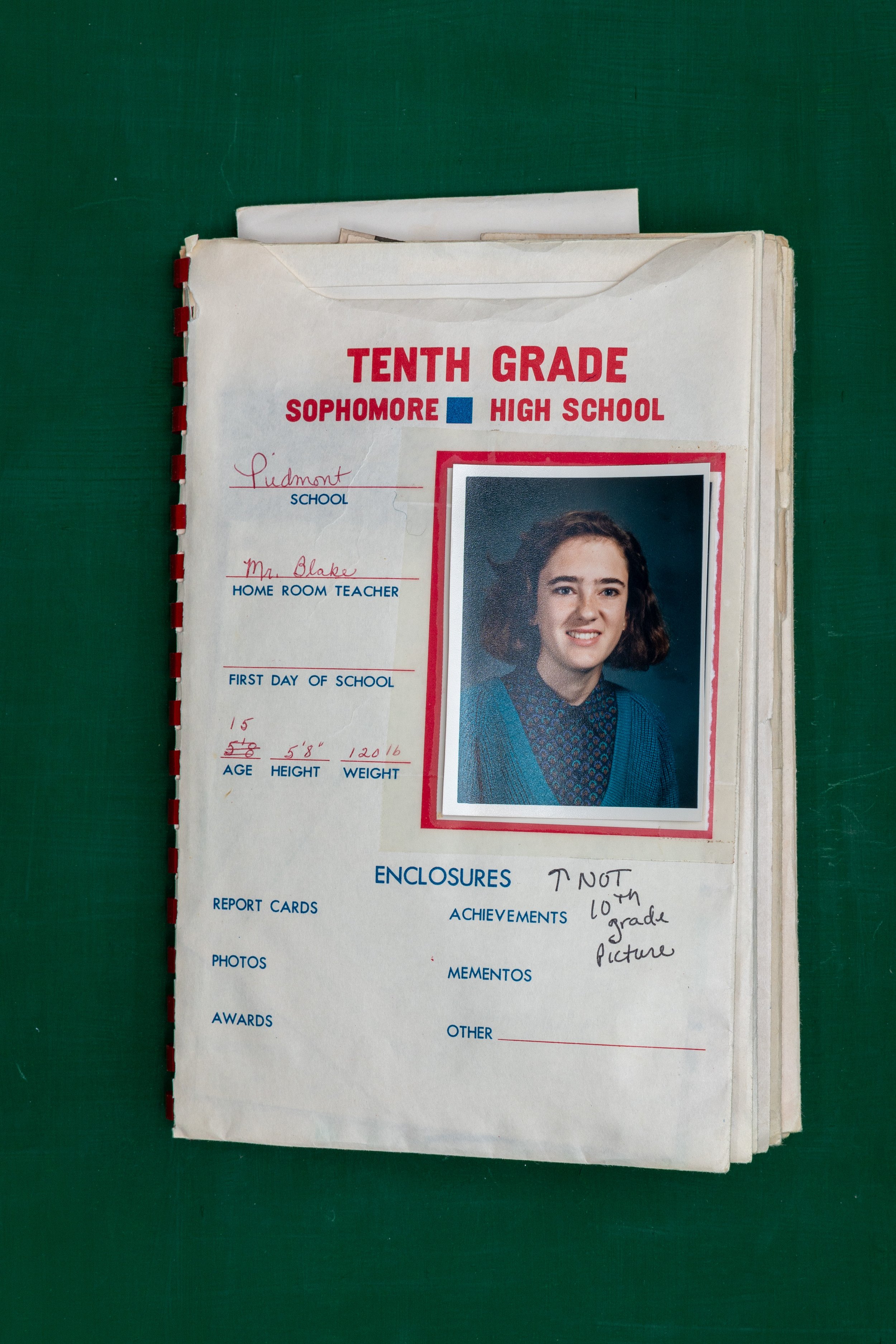

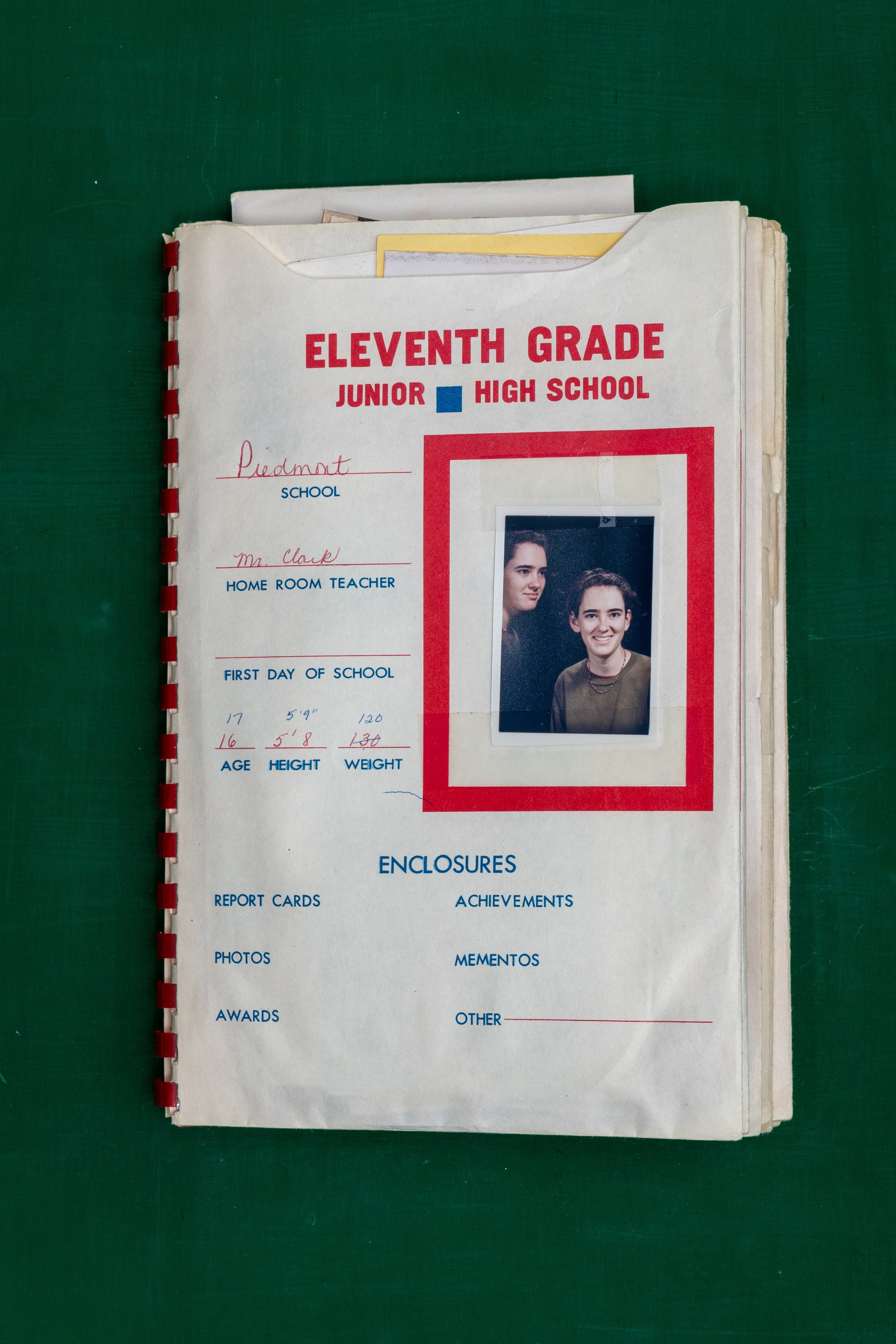

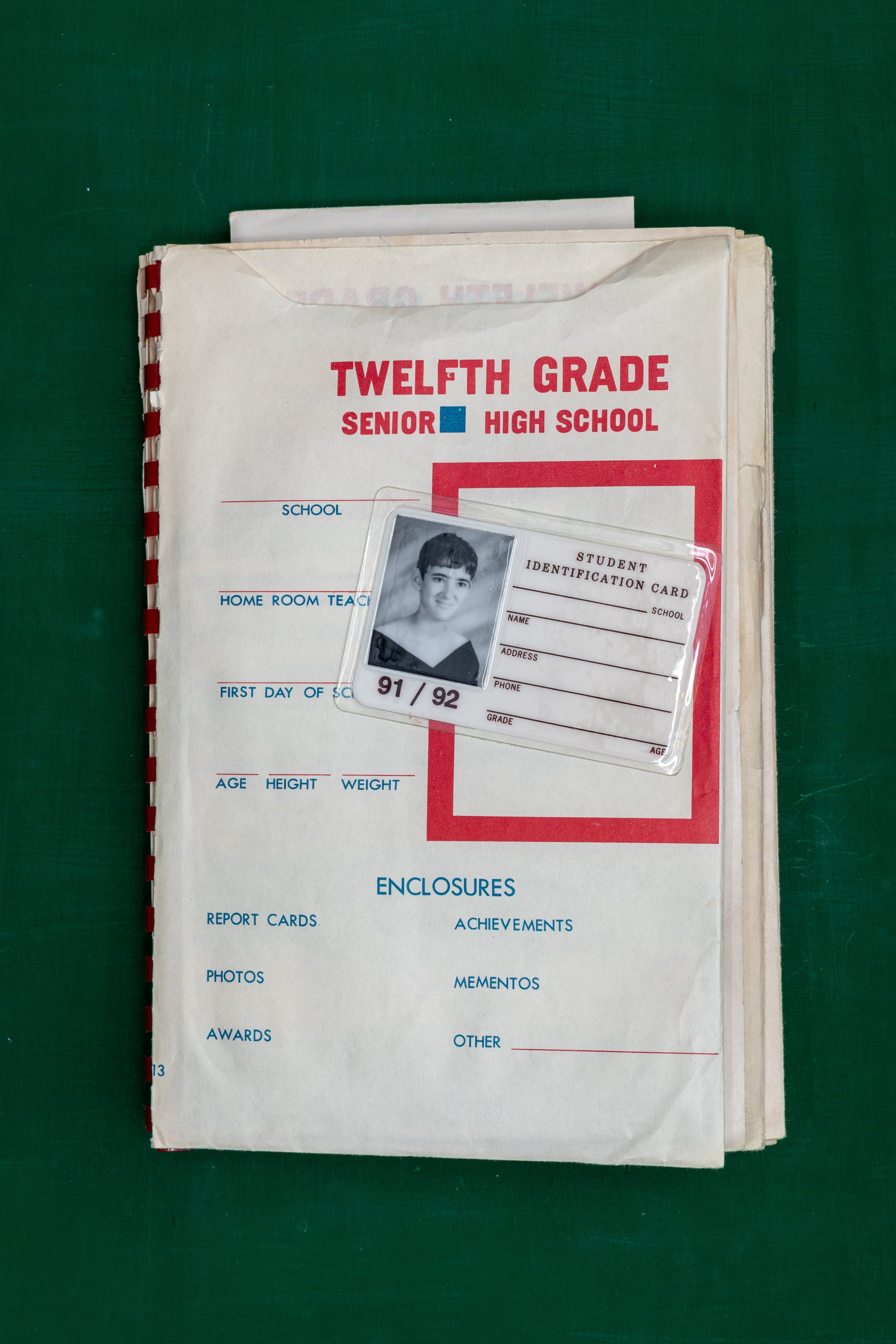

SCHOOL YEARS

My mother was a bookkeeper by profession, but her real passion was her role as the family archivist. These are the pages from a book that she used to keep track of my progress through the school years. Each page in the book is an envelope that holds my report cards, drawings, letters from teachers, newspaper clippings, and other ephemera from my youth, as well as those wonderful school photos that serve as documentation of a metamorphosis from child to adult.

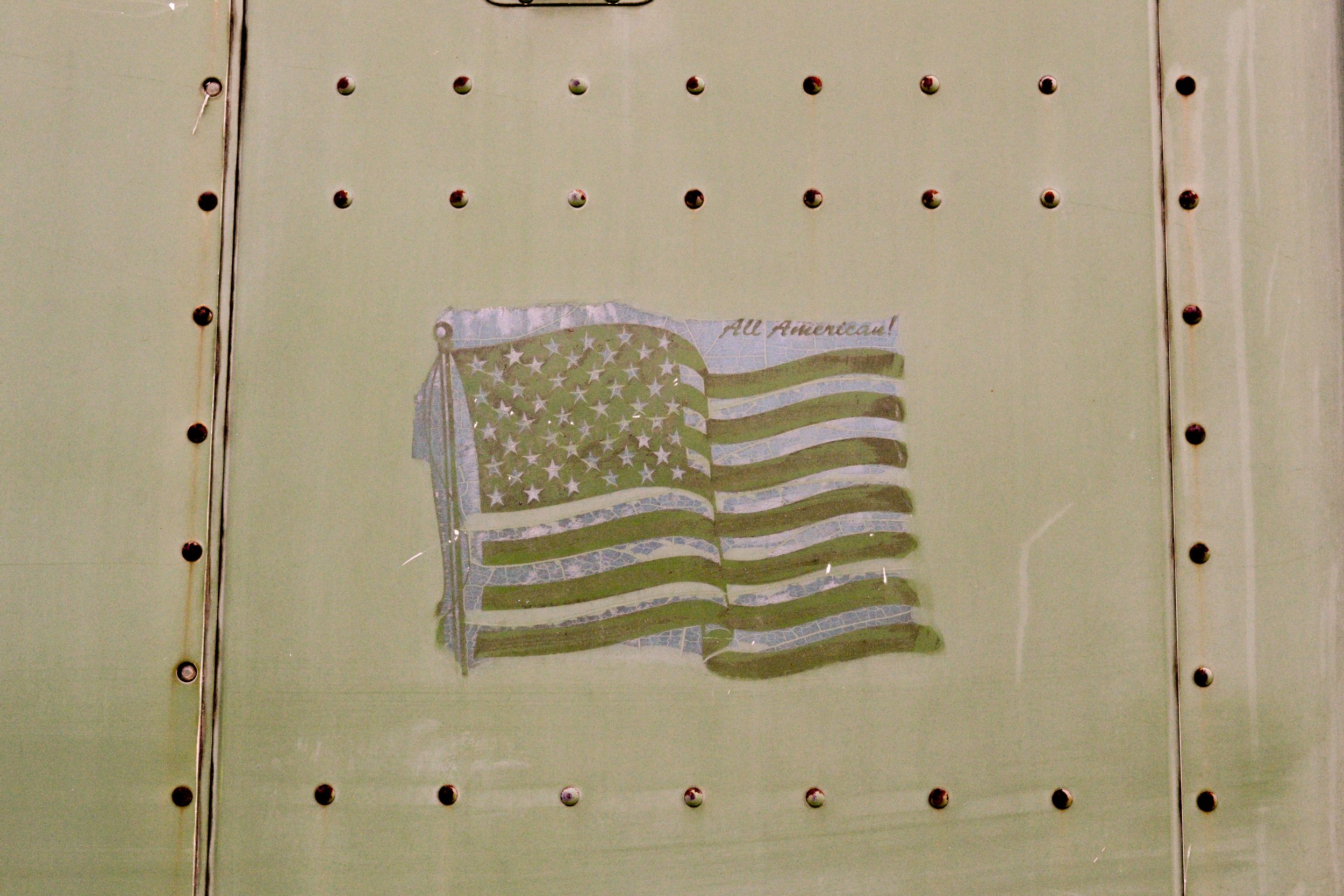

HOMEPLACE

They say that you can never go back home, but I disagree. I hadn’t planned on staying long, but after a couple of weeks I found that I did not want to leave. I took pleasure in roaming the woods where I played as a child. Maybe I was looking for myself, and maybe I found myself and discovered that I was—and was not—who I thought I was, or would be. The trees guided me, the wind talked to me. Some days the constructed world melted all around me as I walked, and I caught a glimpse of a different world.